The Covid – 19 pandemic has triggered, or in some cases accelerated, a transformation of cultural and reading habits, as emerges from the research published in the white paper published by the Centre for the Book and Reading (CEPELL) in collaboration with the Research Department of the Italian Publishers Association (AIE) and the Istituto Poligrafico e Zecca dello Stato “Dall’ emergenza a un piano per la ripartenza. Libro bianco sulla lettura e i consumi culturali in Italia (2020-2021)” (From emergency to a plan for recovery. White paper on reading and cultural consumption in Italy 2020-2021).

Here we published some extracts from Part 2 of the study providing key figures on reading habits and purchase behaviors during the pandemic.

The full study, in Italian, is available online on the CEPELL website

The effects on reading

So, what happened to reading in Italy during the pandemic? What about pre-existing reader behaviour, such as the growth of e-commerce, e-books and audiobooks and the shift from traditional media to online media, all of which the current situation has significantly accelerated? Will we see a return to pre-lockdown trends?

As part of the current research project, the two “Reading during the Pandemic” surveys attempted to answer these and other questions. An initial survey conducted in May 2020, following the end of the first lockdown in Italy, provided a sense of the situation during the months of shutdown. A second survey in October, covering the months that followed, gauged the mood of Italian readers ahead of the more deadly phase of the pandemic’s second wave.

A comparison of the two surveys with those conducted previously by the AIE Observatory provides an initial snapshot that can be used to track reading behaviour before, during and after the (relative) return to normality.

May’s survey showed Italian readers “distracted” by the pandemic, with little time for reading books as they followed the huge volume of news with which TV, news sites and social media relentlessly assailed understandably overwhelmed citizens. The data from October paint a different picture, with reading growing across all forms.

This confirmed what interviewees in May had said in answer to one of the survey questions. There was a 4.7-point positive difference between the share of those anticipating a future increase in their reading and the share anticipating no change (or a decrease). In this regard, reading stood out from all other forms of cultural consumption, which reported negative values.

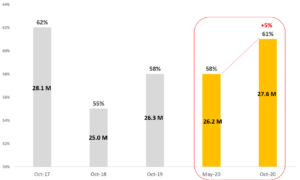

“Overall” reading (books, e-books, audiobooks) between May and October grew from 58% of Italians aged 15-74 years to 61%. In absolute terms, it went from 26.2 million people to 27.6 million (+5%).

“Overall” reading (books, e-books, audiobooks). Figures in %; population base (15-74 years)

All forms of reading grew:

- Books, which had struggled the most during the first phase as books and libraries closed (from 53% to 55%).

- Digital formats: e-books rose from 26% to 30%; and audiobooks (excluding podcasts) from 11% to 12%.

It is worth highlighting that the latter had already grown in May compared to the last survey conducted in 2019: e-books by +4%, and audiobooks by +10%.

From May to October, reading began to grow more consistently once again. Readers of at least one book every three months stood at 37% in 2019, fell to 32% in May and rose again to 38% in October.

We also saw something else of note: book-only readers fell: from 39% in 2019 to 28% in May 2020, and to 29% in October. These figures are all the more evident when we look at the trend among readers only, respectively: 59%, 52% and 48% to October 2020.

We need to understand two things over the next months. (i) If this “discovery” of digital reading means traditional readers have also discovered new features and aspects that enhance their experience and could strengthen/accelerate the changes seen. (ii) This shift towards digital didn’t impact on the number of non-readers, which have actually grown. “Absolute” non-readers (as a moving average and not as a precise comparison between different periods of the year) made up 36% of 15-74-year-olds in 2018, 35% in 2019 and 41% in 2020 (surveyed in March, May and October). “Digital” readers only partly compensate for the decreases.

In this case it appears that the social emergency Italy faced over the nine months in question had a strong catalyst effect in the first phase, accentuating reader behaviour around access to digital published content that already existed, but in a less pronounced form[1]. In the next phase, we see a return to printed media but not to the previous extent (in October).

On a side note, we thought that reading would increase throughout the period of lockdown spent at home. But reading is an activity that requires calm and the right space or the right time.

Between March and April, none of these conditions applied. Reading a book (or an e-book, or listening to an audiobook) is an activity that – even in normal times – Italians generally spent less than an hour a day doing continuously. During this time, reading was displaced by many other activities: following news, watching TV, intensively using smartphones and apps, social media, instant messaging and video conferencing. These activities gradually ate into more and more of our time. What’s more, in March and April new activities began to occupy home life such as distance learning and smart working; meanwhile, care activities expanded and the time needed to carry out essential tasks outside the home, such as shopping, grew.

Out of 21 activities monitored in May’s research regarding the prior two months, 34% of respondents said that reading was one of the activities they had done “more often” than in the past, with 16% saying they did it “less often”. Almost half (47%) of those who hadn’t read any book between March and April gave a lack of time as a main reason; 35% cited a lack of quiet spaces (at home) to read; 33% said that a state of worry “had stopped them wanting to read”; and 32% said they had spent more time reading newspapers and magazines (print and online) compared to books.

So, at home during the lockdown book reading (e-books, audiobooks) had been pushed aside by other activities, with people struggling to find time.

But somehow people did find time. An 18-point positive gap separates the 34% who said they spent more time on reading and the 16% who said they spent “less time”. This is a different, and perhaps more significant, measure than the number of people reading at least one book, which fell in contrast.

We are, it appears, witnessing an even greater fragmentation of reading behaviour: less widespread than previously but, among many people, more intensive.

Effects on purchasing behaviour

The reasons behind people’s book choices underwent a change between 2019 and 2020 (October). The combination of interests and personal passions (subjects and authors) continues to dominate, but other factors grew or decreased in importance with relation to the wider external context.

Discounting declined as a reason given from 20% in 2019 to 14% currently, almost certainly due to new regulation which came into force in Italy in February.

Book store visits returned to 2019 levels (33%) in October, following an obvious collapse (to 19%) during the period when physical visits were not possible. However, bookseller recommendations fell from 10% to 6%, in part due to the closures and, even after stores reopened, due to difficulties in interacting with booksellers while observing social distancing; other factors could also have played a part, such as booksellers having less information to give customers following changes to “new release” schedules and promoter visits.

In contrast, recommendations and information from online bookstores as an influence on book choices rose from 1% in 2019 to 5%, becoming, for the first time, a significant factor.

Media influence continued to grow, with significant growth in online (social media, online bookstores, publishers etc.).

If we look at where sales took place, the reader survey confirms what was already evident from market data:

- 20% of readers stated they purchased books from bookstores in May. This rose to 47% in October (via home delivery and book stores incorporating newsagents, and therefore exempt from closure), but this figure stood at 54% in 2019; larger retail outlets, such as supermarkets, and newsagents went from 11% to 23% (21% in 2019).

- Even the few book fairs in the period (often at a local level) seem to have attracted readers, despite restrictions on holding and attending them. They were cited by 5% of interviewees.

- Those giving the source of books they read as presents, home collections, library loans or book swaps with friends or acquaintances fell to 41% in October from 57% in May. It is interesting to note how during lockdown readers took up exchanging books socially, partially compensating for the reduced opportunities for purchase. The figure in October remained a great deal higher than the figure in 2019 (34%).

- The only trade channel to show significant growth was online. In 2019, 31% of readers said they bought the books they read online. In October the figure stood at 38% (after hitting 39% in May): this is equivalent to just under 11 million readers, three million more than those estimated the year before.

Readers buying e-books from dedicated platforms such as Amazon.it, IBS.it and laFeltrinelli, Kobo.com, etc. were also on the rise. They grew from 23% in 2019 to 27% in October 2020. For the most part, these were readers supplementing their “print-based” diet with digital. It is important to clarify that although the number of those reading grew, exceeding a quarter of readers, the number of those reading exclusively in digital formats remained at 5%-6% of the total. In the great majority of cases, it is book readers who are moving towards e-books.

As for books, which also recovered after May, there was a return in October to levels very similar to 2019.

People not only returned to reading, but also to purchasing, albeit with a different mix to previously – more digital, and more digital combined with books.

Changes to how time is spent

Amid the many other changes there was also a shift in how time is spent. As noted before, this has an effect on a key element of competition between businesses, and thus between sales channels and single stores, who are looking to offer their customers time-saving benefits as a differentiator.

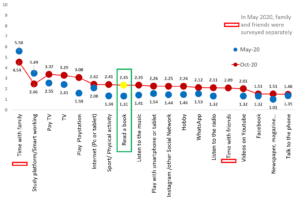

In May, a great deal of time was occupied by caring for the family (readership among females was also down), by smart working and by remote learning. By October, this time had been freed up: interviewees declared that they had reduced their time “with the family” by around one hour and were also spending an hour less smart working or remote learning.

The “time saved” was thus redistributed across various other activities. This included reading, which interviewees said they spent around one hour more on.

Trends in the average number of hours spent on each activity. May – October 2020*

Average figures among those spending at least a few minutes a day on each activity

Forecasts of behaviour

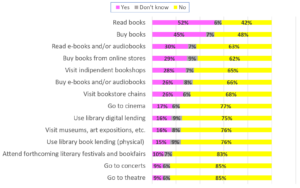

This last part of the research should be treated with the same caution with which all survey forecasts should be treated. Only time will tell if the results are accurate. That said, going on interviewee responses it becomes clear that reading (across its different forms, from books to e-books) and the different options for buying books exceed all other cultural activities.

While 45% anticipate buying books in the three to four months after the survey, and 52% anticipate reading them, only 17% are planning on going to the cinema, 16% to shows or museums and 9% to concerts (although restrictions on the latter activities will certainly have influenced the answers). The responses are to an extent obvious. They are related, on the one hand, to respondents feeling safer in book stores relative to Italy’s pandemic rules, and, on the other, to the comparison with environments such as cinemas and theatres where people enter as part of a wider crowd and for a longer time than is the case in stores.

If anything, it is interesting to note for the future that 10% of people in October were intending to return to book fairs or literary festivals. The figure itself is not revealing, but it is interesting to see how deeply embedded these events are in the reading population.

Purchasing forecasts and attendance at cultural locations in the next three to four months

Figures as % of the population, ordered by “definitely yes”

|